Direct Discrimination occurs when a person treats another less favourably than they treat (or would treat) others because of the protected characteristic.

Direct Discrimination occurs when a person treats another less favourably than they treat (or would treat) others because of the protected characteristic.

The Protected Characteristics are:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion or belief

- Sex

- Sex orientation

Direct discrimination is unlawful. However, it may be lawful if the following applies:

- If the protected characteristic is age and the less favourable treatment can be justified as

proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

- If the protected characteristic is disability, and the disabled person gets treated more favourably than a non-disabled person.

- Where the Equality Act provides an express exception (such as positive action, and occupational requirements).

What is Less Favourable Treatment?

To determine if there has been less favourable treatment a comparison must be made with other workers that are in similar circumstances, but do not have the relevant protected characteristic (you therefore have to identify a comparator

).

If the treatment puts the worker at a clear disadvantage compared with others, then it is more likely to amount to less favourable treatment. Less favourable treatment can also involve being deprived of a choice or being excluded from an opportunity.

There is no requirement to experience an actual disadvantage (such as financial loss). It is enough if the worker can reasonably say that they would have preferred not to be treated differently. However, treating people differently does not of itself mean there was less favourable treatment. For example, men and women may be asked to wear different uniforms and if the standards set are equivalent, this is unlikely to be less favourable treatment.

An employer is not able to balance or offset

less favourable treatment against more favourable treatment, for example offering extra benefits to make up for demoting someone.

For direct discrimination because of pregnancy and maternity, the legal test is whether there was unfavourable treatment, meaning there is no requirement to carry out the comparison exercise such as with less favourable treatment.

When the protected characteristic is race, any deliberate segregation of workers from other workers of a different race is automatically less favourable treatment and there is no need to identify a comparator. The segregation must be a deliberate act or policy. It will not be direct discrimination if it has occurred inadvertently. If there is segregation linked to any of the other protected characteristics this may also amount to direct discrimination, but it will be necessary to establish that there was less favourable treatment.

Direct discrimination can take place even if the employer and worker share the same protective characteristic.

Direct Discrimination – Because of

a Protected Act

For there to be direct discrimination, the less favourable treatment needs to be because of the protected act.

In other words, the protected characteristic needs to be a cause of the less favourable treatment, but it does not need to be the only (or main) cause.

In some cases the link between the less favourable treatment and the protected characteristic will be clear, but this is often not the case.

The main evidential issue is usually establishing a link between the protected characteristic and the less favourable treatment. There is a requirement to look at why the employer treated the worker less favourably, but establishing their motivation is often challenging.

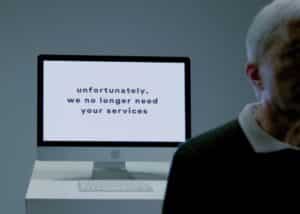

A person gets to the third and final stage of the interview process. They feel like the interview goes well and during the final discussion, they explain to the company that they have a disability. The applicant was not offered the job and it was offered to someone else that does not have a disability. The applicant believes they were not offered the job because of their disability. However, it will be necessary to look at why the employer offered the position to someone else to determine if there was direct discrimination. It may be difficult to determine if the reason was because of the disability or because the other application (without the disability) was a better candidate.

If a person acts on discriminatory grounds, the reason why is irrelevant, this will still be direct discrimination. Therefore, direct discrimination is unlawful, no matter what the person’s motive or intention or if the less favourable treatment was conscious or unconscious.

A company seeks to recruit a new manager and decides to interview two men and two women, thinking this is fair. The top three applicants are female, but only the top two are interviewed. The women’s application that was ranked third was not interviewed, because the company interviewed the best two male and best two female candidates. Even though the company believed this was fair, a female candidate missed out on an interview due to her gender, meaning this was likely to amount to direct discrimination.

Direct discrimination can also occur if the less favourable treatment is based on a stereotype, even if the stereotype applied is not accurate. The objective of the legislation is to treat people as individuals and not be assumed to be like other members of a group.

In certain circumstances, the worker receiving the less favourable treatment because of a protected characteristic does not have to possess the characteristic themselves. The worker might be associated with someone that has the characteristic or they may be wrongly perceived as having the characteristic.

Discrimination by Association

If a person is treated less favourably because of their association with another person who has a protected characteristic, this may also be direct discrimination.

However, this does not apply to marriage and civil partnership or pregnancy and maternity (although in the case of pregnancy or maternity, a worker treated less favourably because of association with a pregnant woman or a woman who recently gave birth, there may be a claim of direct sex discrimination by association).

A manager treats a worker who is atheist less favourably when he finds out that the worker’s best friend is muslim. This could be direct religious discrimination by association.

Direct discrimination can also occur if someone refuses to act in a way that would disadvantage a person that has (or the employer believes has) a protected characteristic or they help or campaign for someone with a protected characteristic.

Discrimination by Perception

If someone is treated less favourably on the grounds of a mistaken belief that they have a protected characteristic, this may still amount to direct discrimination.

A worker has been off sick and tells her employer that she is to receive a scan on the basis there is a suspected brain tumour. The employer decides to dismiss this person, believing they have a brain tumour and thus are disabled. The scan reveals there was no brain tumour and therefore no disability, but this may still amount to disability discrimination by perception.

An employer rejects a job application from a British man because he has an Asian-sounding name, wrongly believing the applicant was Asian.

You can read our case study of a discrimination by perception claim HERE.

Comparators

Excluding cases of racial segregation or pregnancy and maternity, for cases of direct discrimination, there needs to be a comparator.

There is a requirement to show that you were treated less favourably than another person that did not have the relevant protected characteristic (this person is referred to as the comparator).

For the comparator to be appropriate, there must be no material difference between the circumstances relating to each case. The circumstances do not have to be identical in every way, but the circumstances relevant to the less favourable treatment are to be the same or nearly the same.

There can be actual and hypothetical comparators. With an actual comparator, you are identifying the specific person you say you have been treated less favourably against.

An employee applies for promotion unsuccessfully. The employee claims they were rejected because of their sexual orientation. The employer argues the decision was based on their experience and qualifications. The comparator must be someone of the employee’s experience and qualification, but who did not share their sexual orientation. In this situation, there will be an actual comparator (the person that was given the promotion).

In practice, there may not be an actual comparator to identify, so the comparison will need to be made with a hypothetical comparator. As with actual comparators, the hypothetical comparators’ circumstances must not be materially different.

Comparators in Disability Cases

For direct disability discrimination, the comparators are to be identified in the same way. However, for disability, the relevant circumstances of the comparator and the disabled person, including their abilities must not be materially different.

Therefore, an appropriate comparator is someone that does not have the relevant disability but also has the same abilities or skills as the disabled person (this is regardless of whether the skills or abilities arise from the disability itself. It remains important to focus on the circumstances which are relevant to the less favourable treatment.

A disabled person applies for a job as a translator. They are only able to translate 50 words per minute. They are rejected for the job because their translation speed is too slow. The correct comparator for a direct discrimination claim would be a person without the relevant disability who was also only able to translate 50 words per minute.

Direct Discrimination – Advertising an Intention to Discriminate

A statement in an advert that the offer of employment will amount to less favourable treatment because of a protected characteristic may amount to direct discrimination. People that are eligible to apply for the job in question will be eligible to claim direct discrimination.

The test for whether an advertisement is discriminatory is whether a reasonable person would consider it to be so. The advertisement does not have to be in the public domain and can include an internal notice or circular.

If an advert is offered to those that are young and ambitious it could be construed that the employer intends to discriminate based on age and an older applicant may be put off applying.

Direct Discrimination – Treating a Person More Favourably

More Favourable Treatment of a Disabled Person

It is not discrimination to treat a disabled person more favourably. For example, you could prioritise job applicants with a disability.

Direct Discrimination – Age Discrimination – Objective Justification Test

An employer can defend a claim of age discrimination if they can show that the discriminatory treatment was a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim – this is known as the objective justification test.

Deciding if the objective justification test is met, is approached in two stages by asking the following questions:

(1) Is the aim of the rule or practice legal and non-discriminatory, and one that represents a real, objective consideration?

(2) If the aim is legitimate, is the means of achieving it proportionate – that is, appropriate and necessary in all the circumstances?

A company has a policy of not employing anyone under 18, because they operate in a hazardous environment and statistics show that younger people are at greater risk of harm. The aim of the policy is to protect the safety of younger people. The aim is likely to be a legitimate one and the age threshold of 18 is most likely a proportionate means if supported by the evidence (using an older age threshold may not have been proportionate).

Direct Discrimination – Occupational Requirements

There is a general exception to the prohibition on direct discrimination in employment for occupational requirements that are genuinely needed for the job.

Direct Discrimination – Compensation

The compensation available in direct discrimination claims is the same as other discrimination claims.

When a Claimant succeeds in direct discrimination claim, an employment may do some, or all of the following:

- Order the Respondent to compensation.

- Make an appropriate recommendation aimed at reducing the adverse effect of the direct discrimination on both the Claimant and the wider workforce.

- Make a declaration as to the rights of the Claimant and the Respondent in relation to the matters to which the proceedings relate.

The most common remedies

available are:

Financial Loss – This covers the financial loss caused by the discrimination. For example, if your dismissal was discriminatory, you would claim for any loss of earnings. If the decision not to offer you a promotion was discriminatory, then you may claim any difference in salary if the promotion came with a pay rise.

Injury to Feelings – An award for injury to feelings is to compensate and not to punish, and is designed to address the anger, distress and upset caused by the discrimination. The award for injury to feelings is separate into three bands:

| Band | Vento (December 2002) | Da’Bell (September 2009) | Updated – Claim brought after 06 April 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top band for the most serious cases, such as where there has been a lengthy campaign of harassment. wards can exceed this only in the most exceptional cases. | £15,000 – £25,000 | £18,000 – £30,000 | £29,600 to £49,300 |

| Middle band for serious cases which do not merit an award in the highest band. | £5,000 – £15,000 | £6,000 – £18,000 | £9,900 to £29,600 |

| Bottom band for less serious cases, such as a one-off incident or an isolated event. | £500 – £5,000 | £600 – £6,000 | £990 – £9,900 |

Personal Injury – This can form part of your claim if an act of victimisation caused personal injury. There is clearly an overlap with injury to feelings.

The Tribunal can also make an award for the following, but these are rare:

Aggravated damages – Aggravated damages are awarded in the most serious cases where the behaviour of the Respondent has aggravated the Claimant’s injury to feelings.

Exemplary or “punitive” damages – Such an award is rare and can be awarded to punish the Respondent, rather than compensate the Claimant. This award is available in limited cases where the compensation itself is an insufficient punishment and the Respondent’s conduct is either:

- Oppressive, arbitrary or unconstitutional action by servants of the government.

- Calculated to make a profit which could exceed the compensation otherwise payable to the Claimant.

Usually, unless there is also some financial loss that can be attributed to the victimisation, the usual award is for injury to feelings only.